A hundred years ago today, the guns fell silent.

That was too late for my great grand uncle, Private James P Rawlinson. A short, spectacled postman from a quiet part of Cheshire, he had already died 19 months earlier in Basra during the Mesopotamia campaign.

The fall of Kut Al Amara in April 1916 (after a long and horrible siege) was a huge embarrassment to the British government. They lost a lot of troops there, mainly from British India. So they just shipped in more.

James P would have been part of the replacement troops, who started in Basra (where he disembarked on 28 September 1916) then fought their way up the Tigris. He and his comrades in the 8th Cheshire would have fought alongside other regiments, many of them again from British India – in fact it looks like the majority of forces weren’t from the British Isles. (I would love to learn more about this if anyone can point me in the right direction.)

According to his military service record, James P had a rough campaign – he was in and out of hospital for the few months that he was in the war. While he died on 20 February 1917, he was actually injured – the gunshot wound to his neck – a few days before, on 15 February.

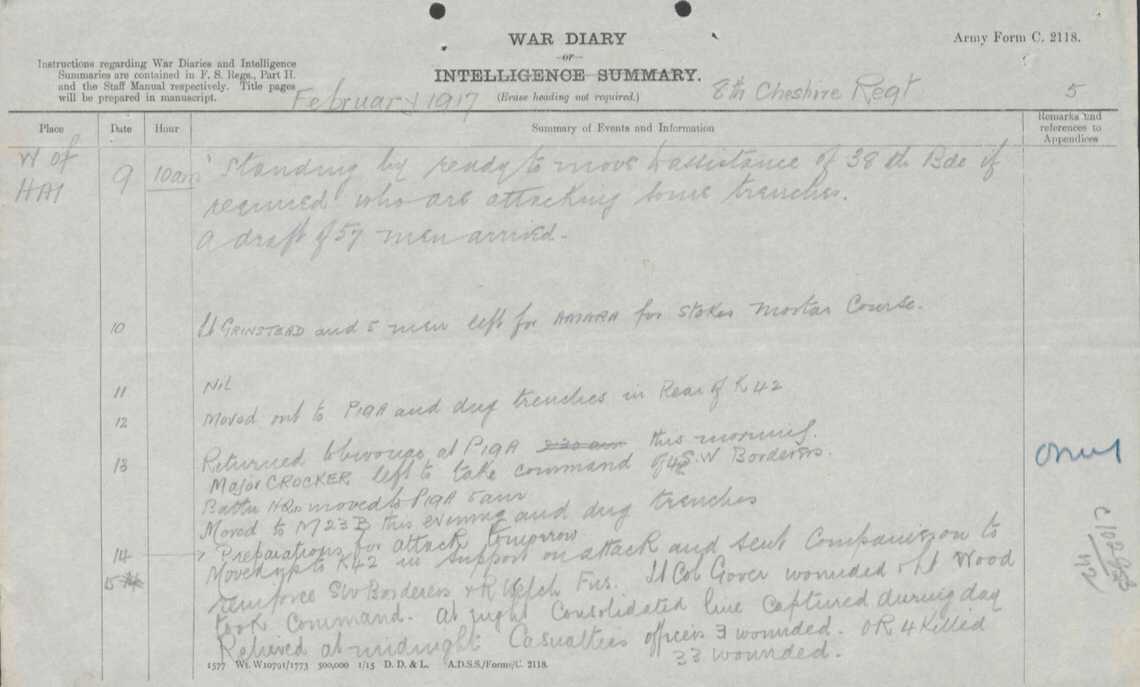

With advice from my friend Paul, I looked up that date in his regiment’s war diary, and it details a mission, with the officers and OR (other regiments) injured. It’s likely he was one of these – see the entry at the bottom:

“15 [February 1917] Moved up to K42 in support on attack and sent companies on to reinforce SW Borderers and Royal Welsh Fus[iliers]. Lt Col Gover wounded and Lt Wood took command. At night consolidated line captured during day. Relieved at midnight. Casualties officers 3 wounded. OR [other regiments] 4 killed 33 wounded.”

Such big things recorded in pencil.

The Mesopotamia campaign was the usual blundering British story of suits in Westminster not understanding how stuff works and not listening to the people who do.

But they did it – Kut fell to the British a few days after James died, on 24 February 1917. They then went on to take Baghdad.

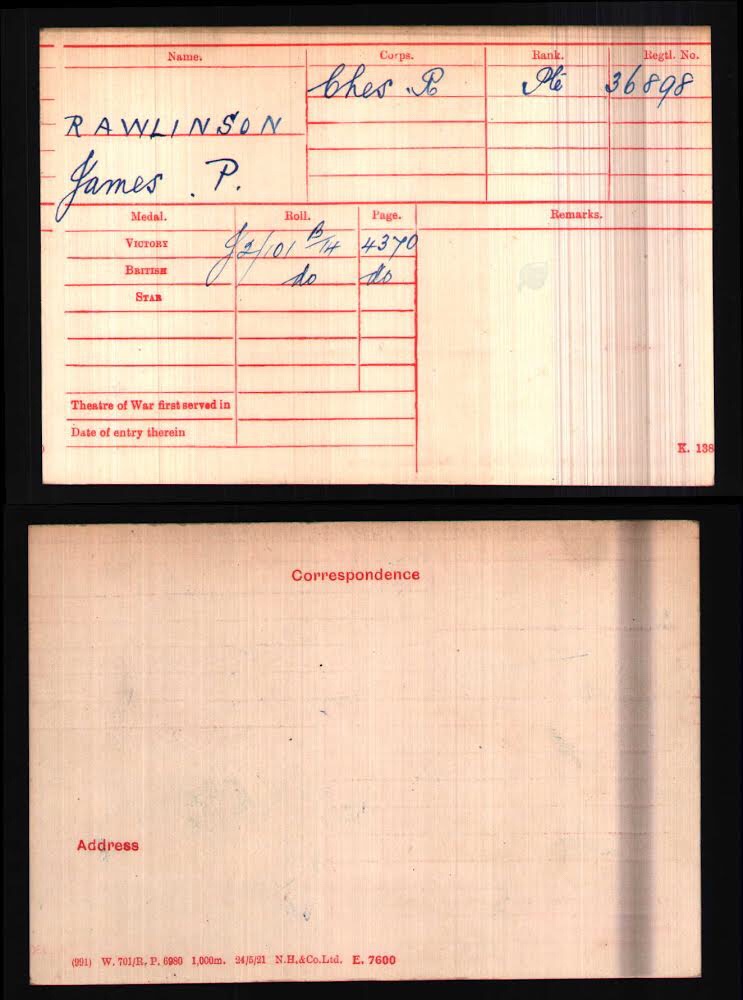

Here’s his medal card:

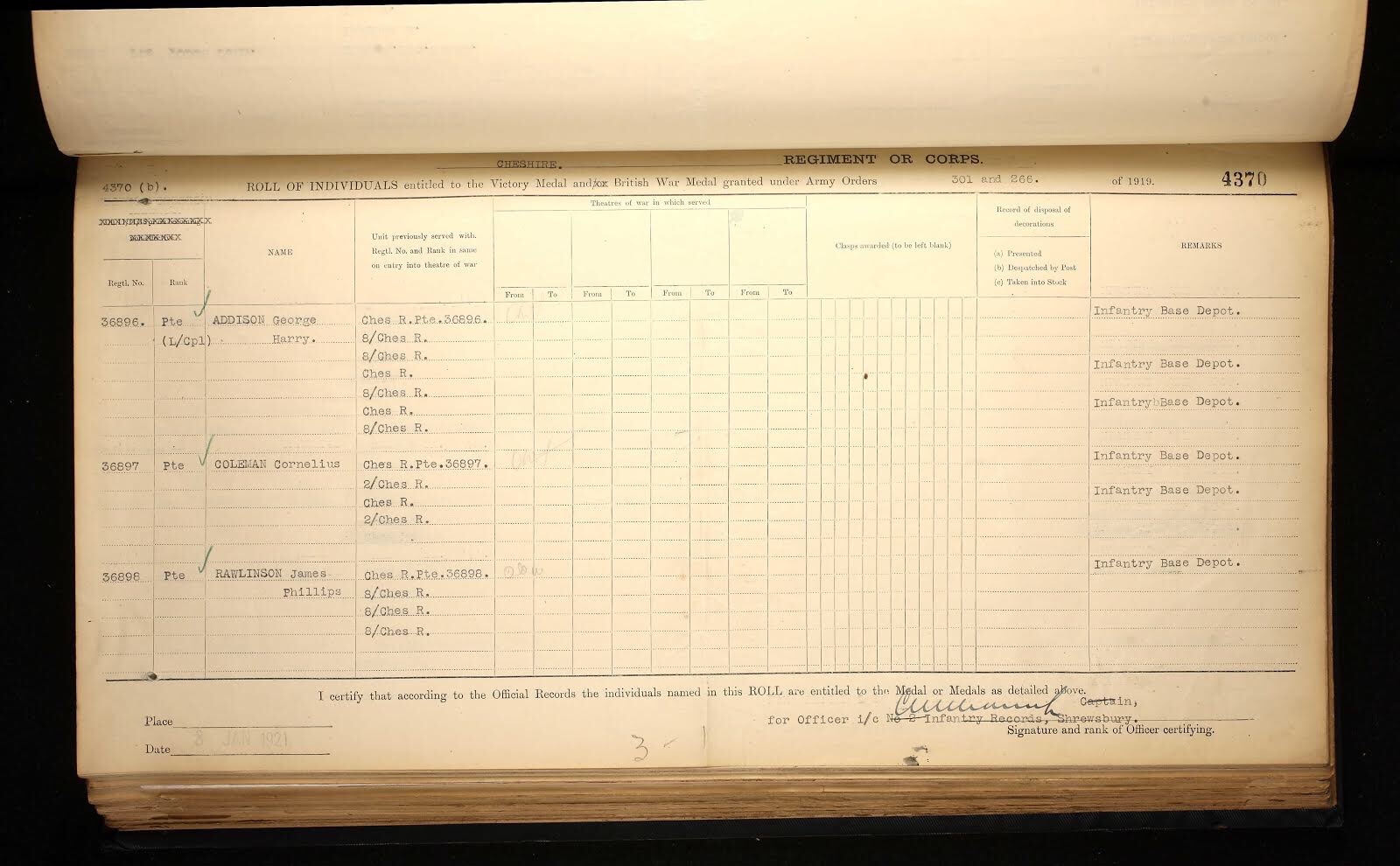

And the medal book that records his honours:

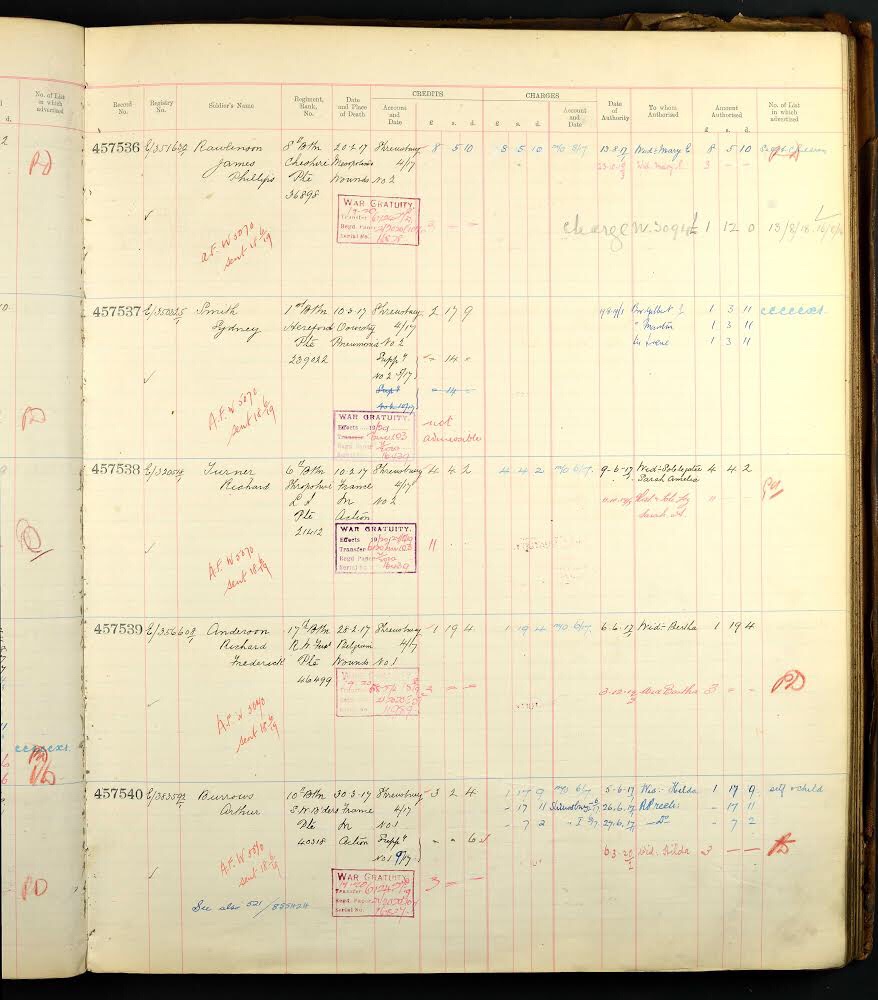

James left behind his wife, Mary, and two children: John, who would have been five when his father died, and Alice, who was just a baby.

Here’s Mary’s widow’s pension record:

There’s also a family myth that he was seen by a friend a few days later. It’s actually entirely possible, in two quite different ways. The first is that he was indeed around for a few days, in hospital, so could have been visited. But that’s not the kind of vision that’s entered family legend.

The second is that the terrain was tough and difficult – lots of mosquitoes, disease, desert heat – and so mirages were common. It seems entirely plausible that a soldier in that situation could have thought they saw him.

Or maybe they did.

So today, I’m thinking of him and his two brothers-in-law, who died on the Western front.

November 11, 2018 at 11:30 am

❤️