How would you like to see a book that someone – probably a monk – wrote by hand in a cold scriptorium a little while back?

Say, a thousand years ago?

Then get yourself over to the British Library, where they have some incredible treasures on display at their astonishing Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms exhibition.

If you’re interested in history, especially medieval history, it’s a simply unmissable, once-in-a-lifetime collection of the most important documents from the Anglo-Saxon period in our country’s history.

(Actually, on reflection, in some cases it’s once-in-a-millennium.)

So there was a big family outing on Saturday, as Ted and I took my dad and the Mothership for their Christmas treat.

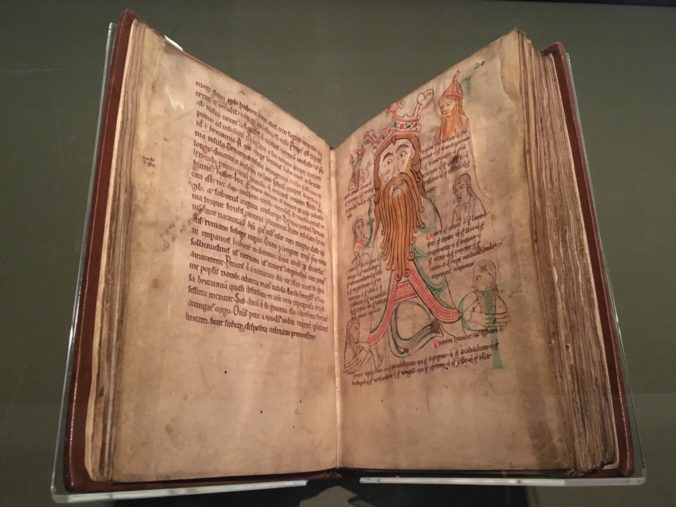

The image above is of Woden, from the Tract on the First Arrival of the Saxons. Woden is basically the German version of Odin, king of the gods, probably because he had the best beard. The Saxons brought their belief in him with them when they came to the British Isles in the fifth century. By the time of the ninth century, when many of the documents in this exhibition were made, Christianity had been adopted, but it still helped underline a king’s power if he could demonstrate a link to the old gods. They did this by claiming direct lineage – the people surrounding Woden above are kings supposedly descended from him.

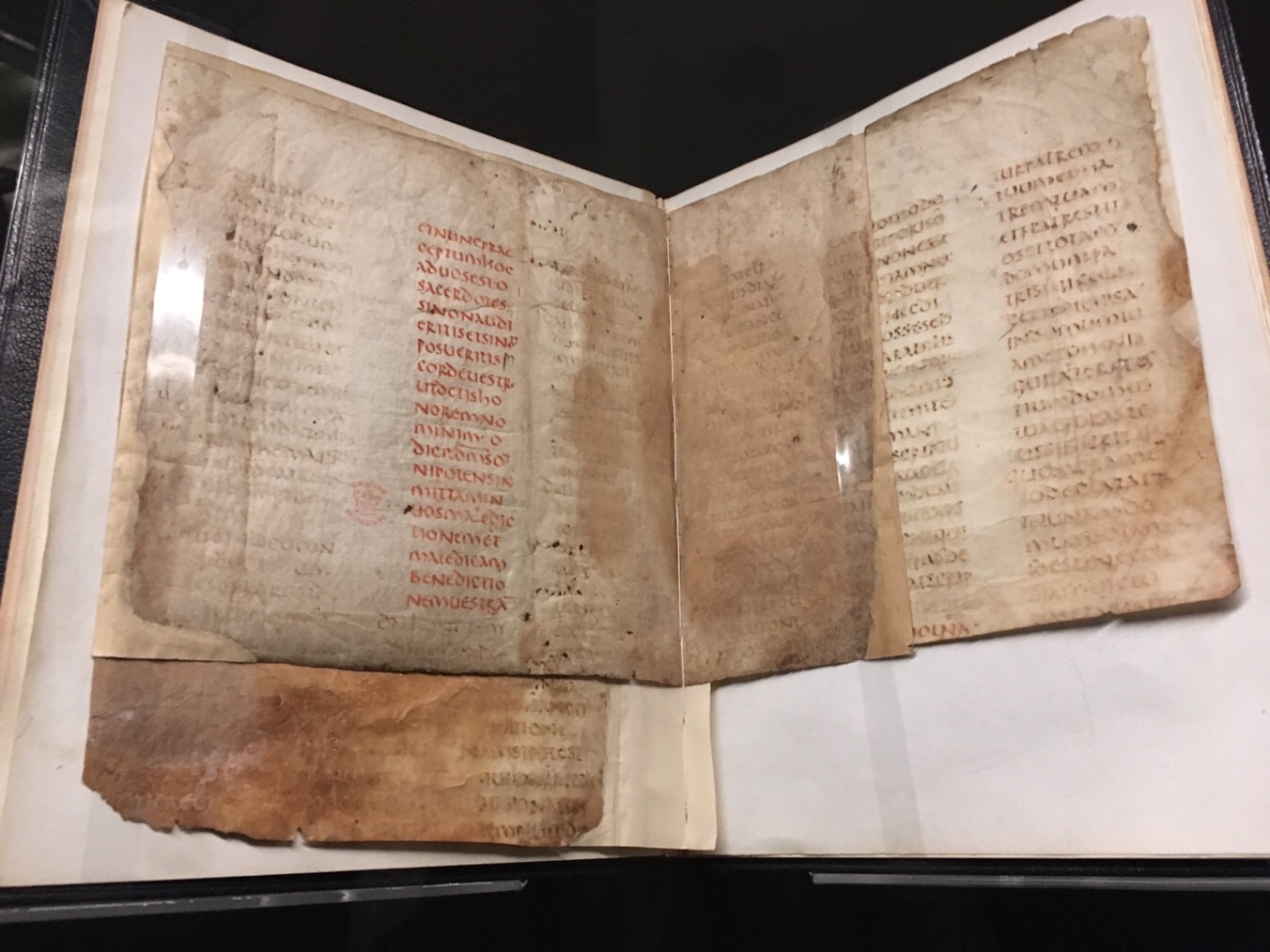

This manuscript above is one of the newer ones on display – it only dates back to the latter half of the twelfth century. Unlike this one below, which was made in North Africa, possibly Carthage, it’s thought in the fourth century:

Yes, that’s right, fourth century. These fragments of manuscript are around 1700 years old. Seventeen hundred years ago, someone was writing these words on this piece of vellum.

???

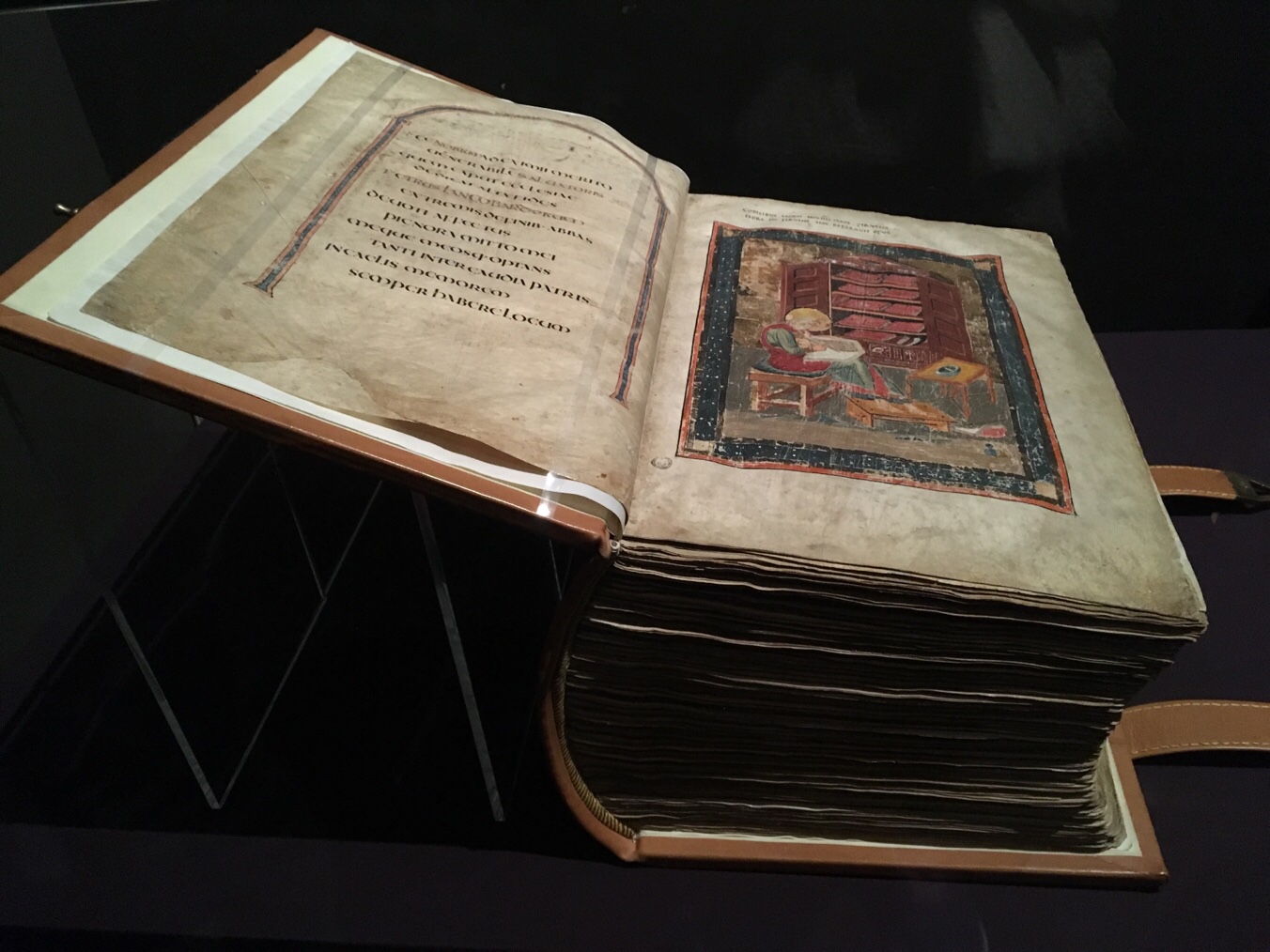

Below is the Codex Amiatinus, a massive bible about three foot by two foot by two foot that’s returned for a visit to the UK for the first time in 1300 years. (It’s been in Italy since it was taken there in 716 as a gift for the Pope.) It was one of three made in Northumbria at a Benedictine monastery (Wearmouth-Jarrow) and is the oldest surviving complete manuscript of the Latin vulgate bible. Look away, vegans – it took the skins of 500 cows to make the vellum for this book:

You wouldn’t fit that in an EasyJet overhead locker.

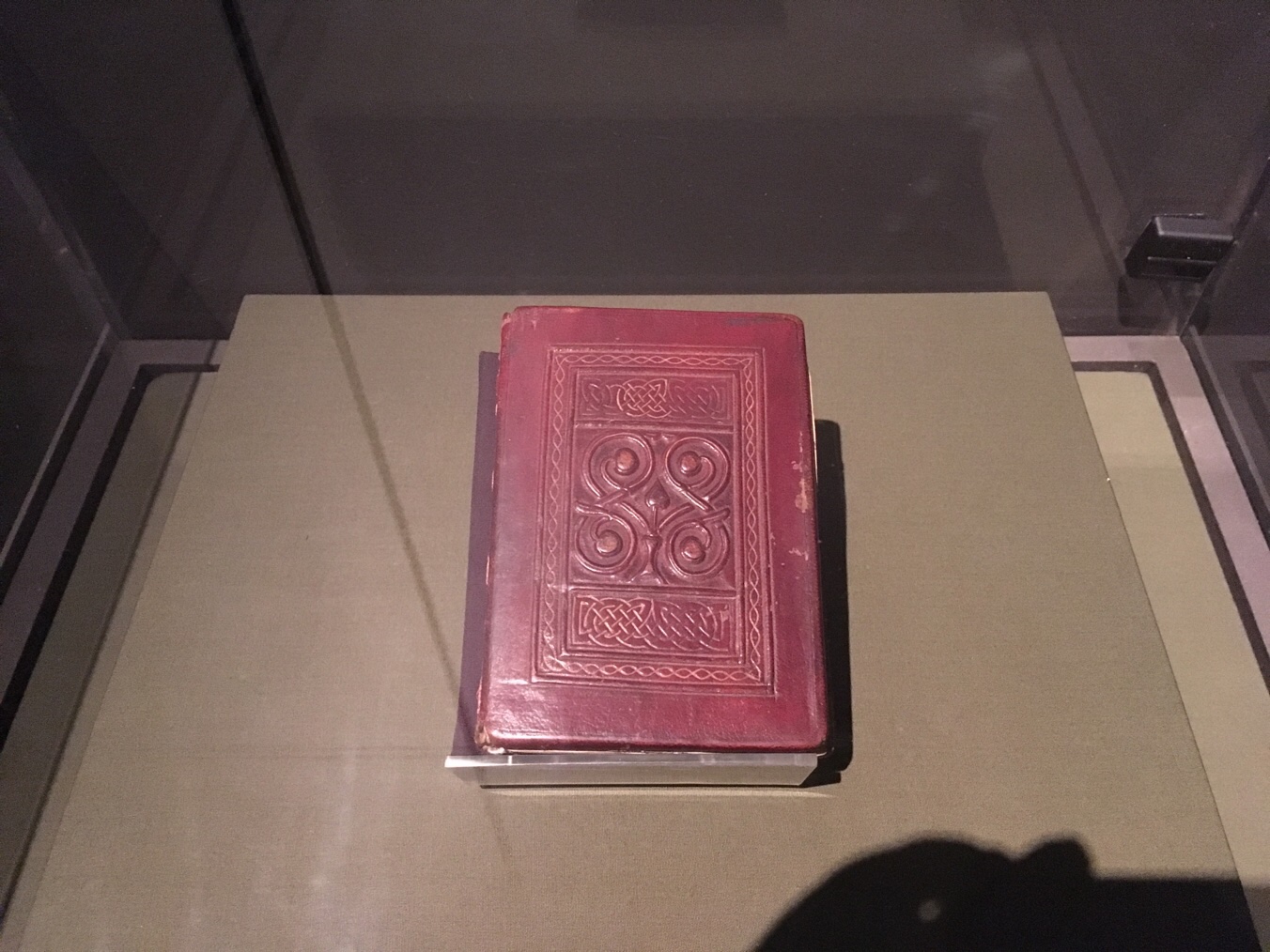

The exhibition is packed full of firsts, oldests and other world-record holders. Here’s the world’s oldest European book still in its original leather binding: The St Cuthbert gospel, also produced at Wearmouth-Jarrow around the same time as the Codex.

Such a pretty little book. But not all of the manuscripts on display are bound. Here’s the Guthlac Roll, from Crowland Abbey in Lincolnshire. It was made around the turn of the thirteenth century and tells the story of the seventh-to-eighth-century St Guthlac and his great deeds.

“They see me rollin’,

They hatin’,

Patrolling and tryin’ to catch me ridin’ dirty …”

Ahem.

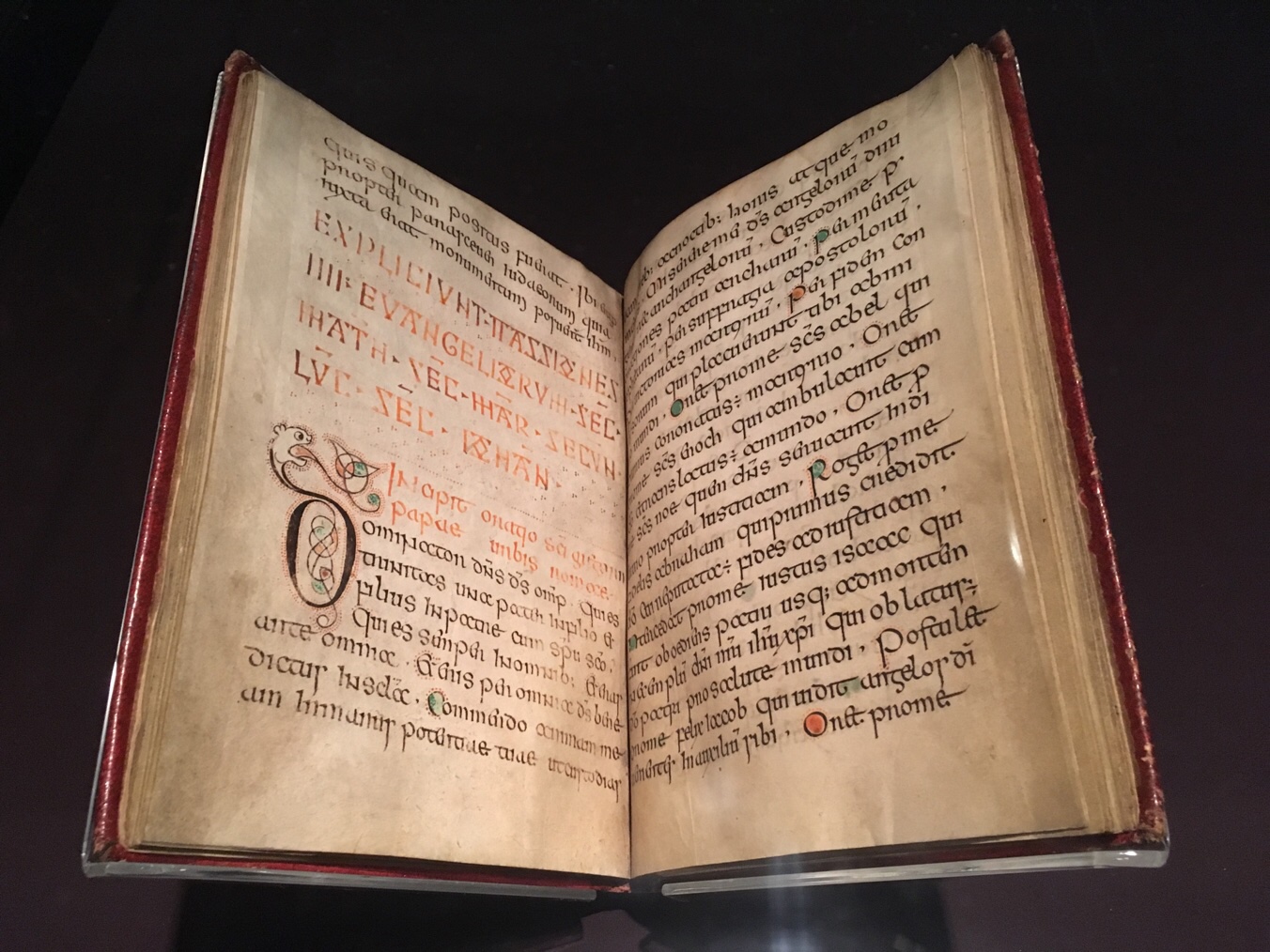

This Mercian women’s prayer book dates to the ninth century and may have belonged to King Alfred’s wife, Ealhswith. I love the beastly decoration.

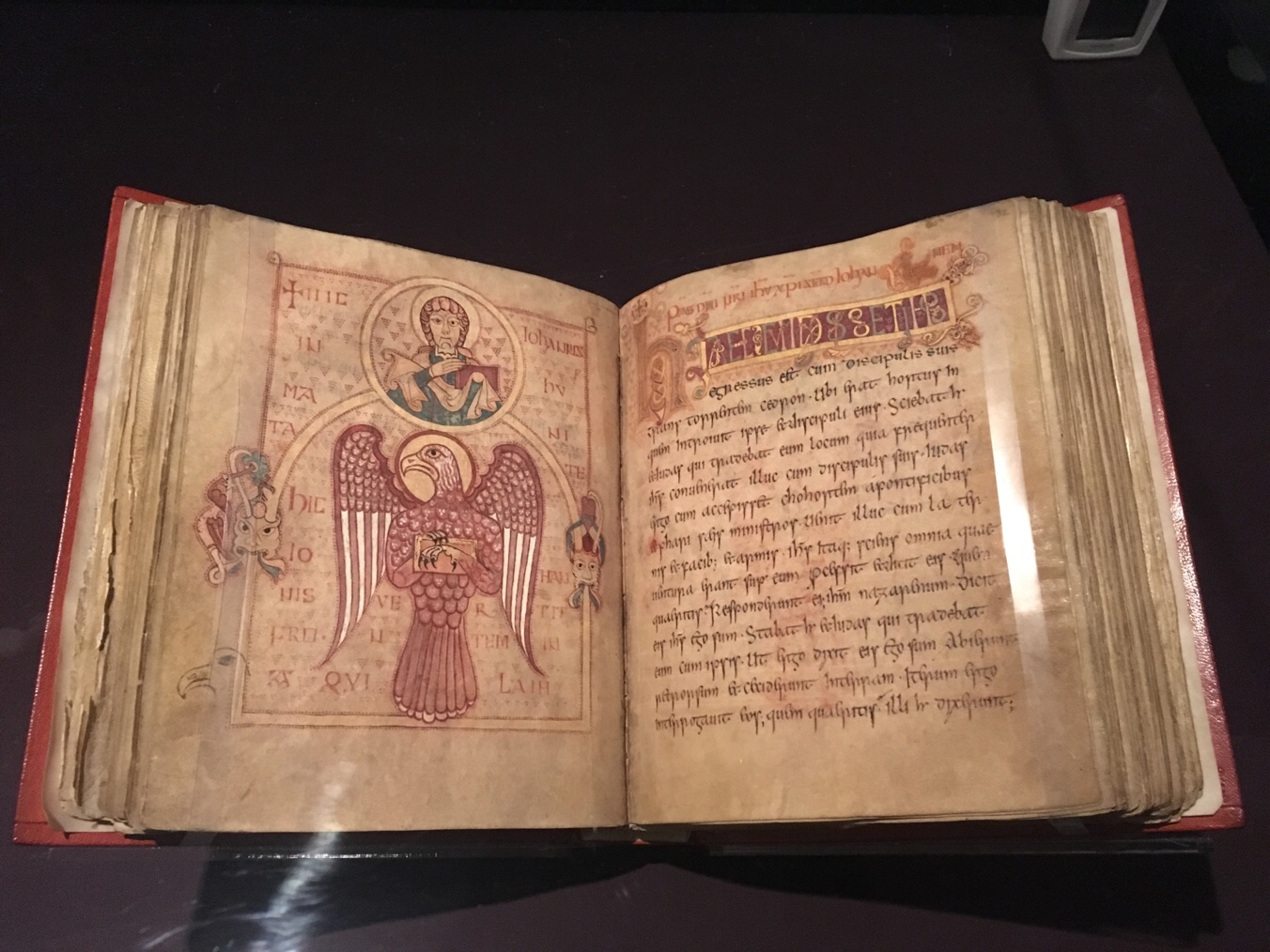

The Mercian prayer book below also dates to the ninth century. It shows St John the Evangelist. Underneath him is his eagle, fiercely clutching a prayer book. Quite meta.

Oh, also, did you know there was a St Chad? Neither did I. Apparently it’s a name used for seventh-century Mercian bishops as well as American jocks. Who knew.

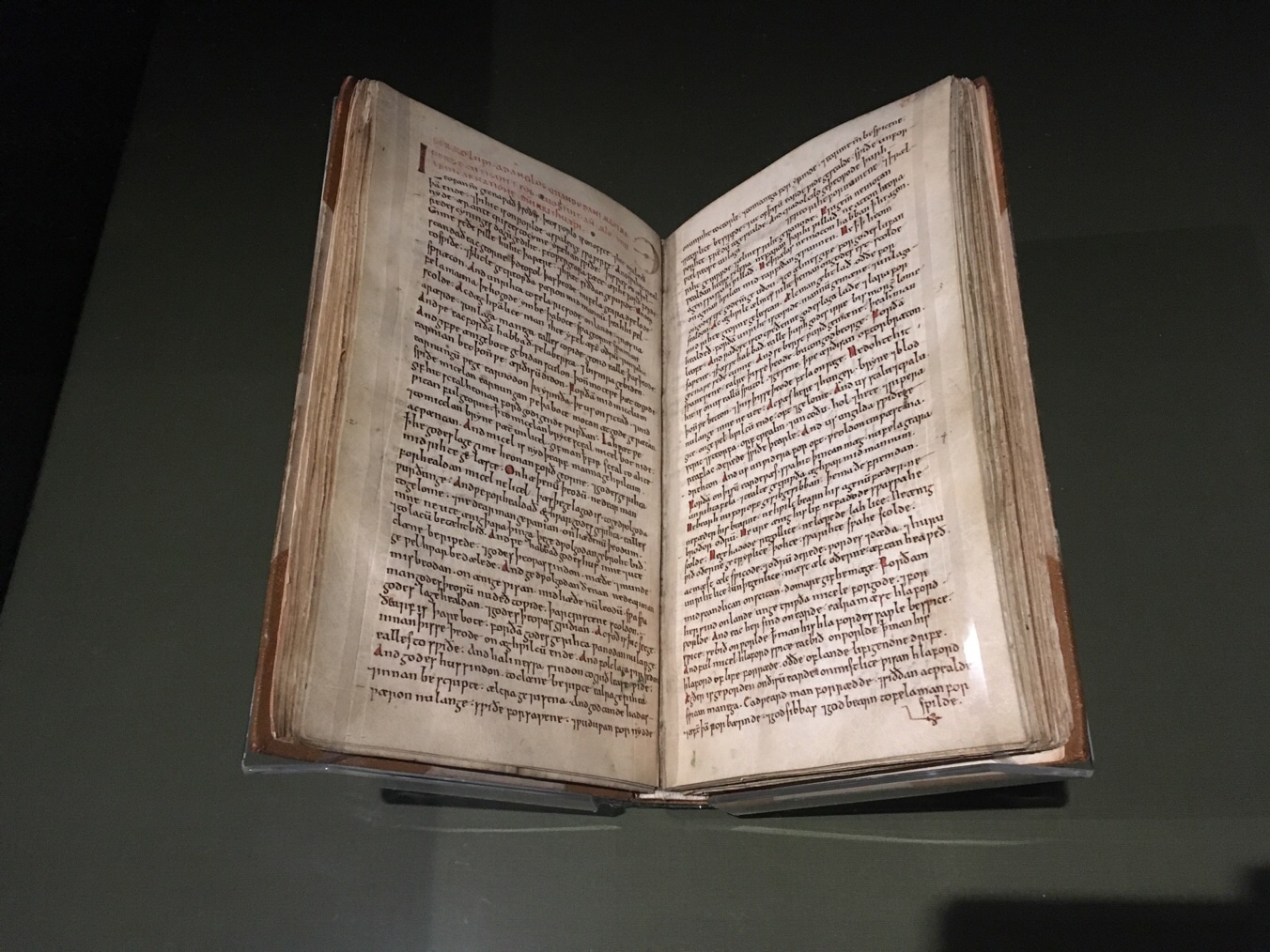

Okay, so this is where I got a little teary for the first time. This is the ninth-century Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, generally the go-to source for English news ‘n’ views in the Anglo-Saxon period. It’s kind of like Ceefax (check out the length of each dated entry) but with more god and Vikings. I spent many happy hours studying it at uni and it was extremely special to see the original, ancient book.

I can’t show you the wonderful herbology book and its amazing blue, spotty serpents or the Old English fragment of Beowulf (BEOWULF!!!) because frankly it got all too exciting and I forgot, but that’s good, because you can go and see them and enjoy them yourself.

(BEOWULF!!!)

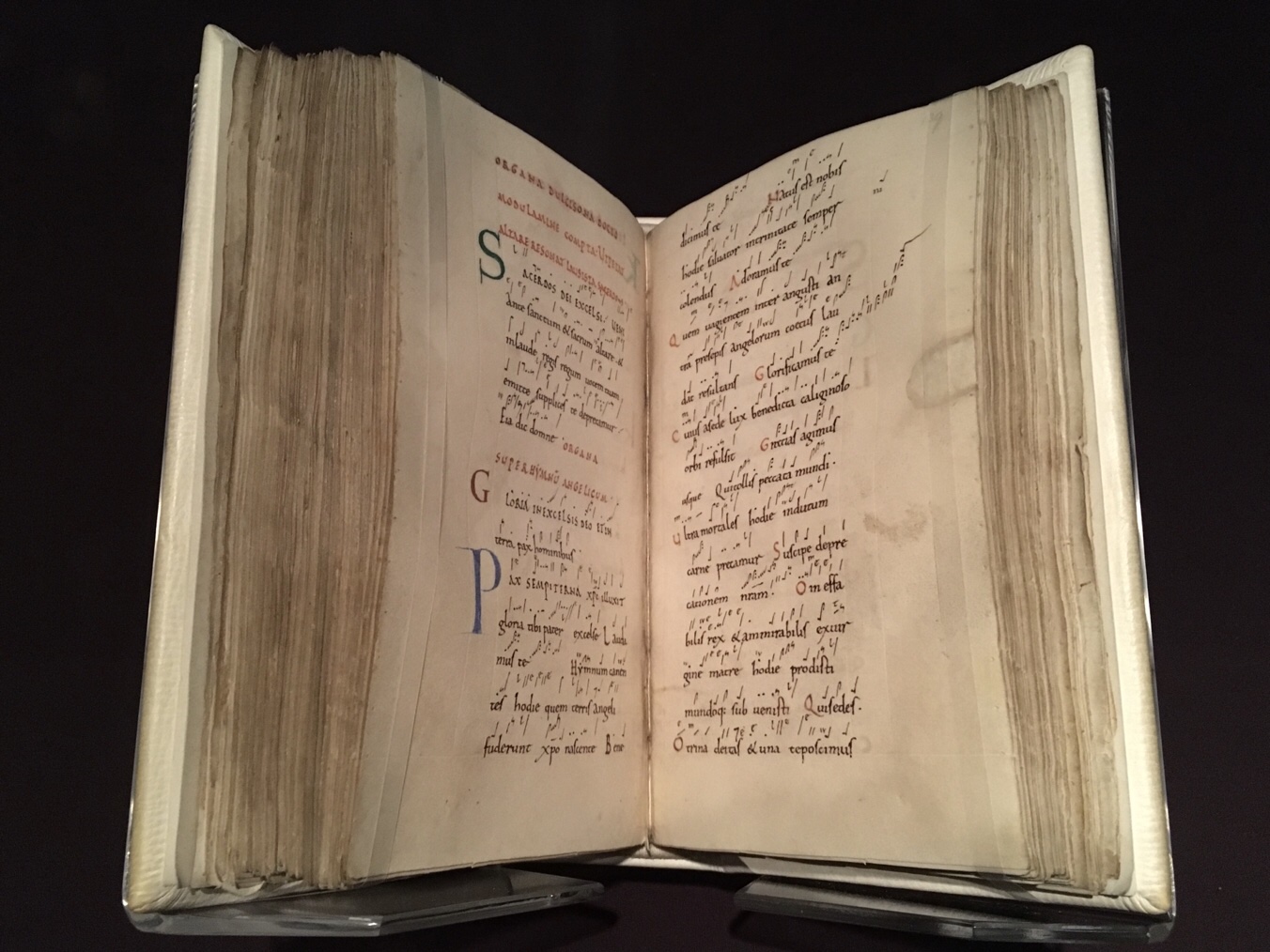

But here are two very sweet manuscripts. They’re songbooks, really. The first is late tenth century:

And the second is early 11th. Look at the musical notation between the lines of text. Completely adorable. These would have been used by monks who chanted at Canterbury (above) and Winchester (below).

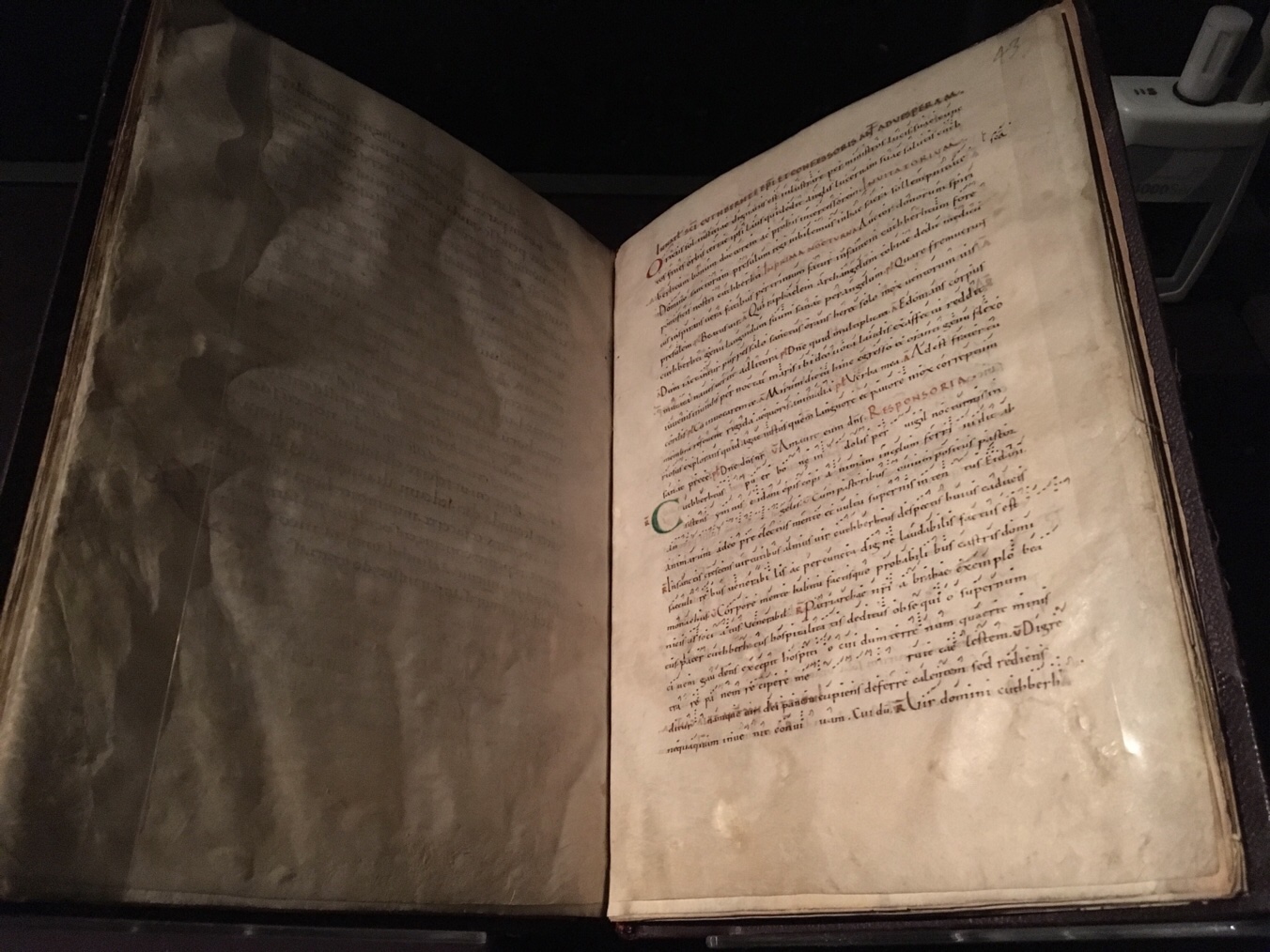

Some clergy preferred to berate people rather than sing to them. Like Wulfstan, Archbishop of York, who – when the Viking raids were at their worst – railed at his congregation in a series of sermons, placing the blame for the disasters befalling them firmly on them and their sinful behaviour. This one, below, is the Sermon of the Wolf, from 1009. It’s a classic.

Right, on to the practicalities. You’ll need to leave a lot of time for this exhibition, partly because there’s so much to see (I’ve not even mentioned the non-manuscript stuff, like the Alfred Jewel ? and pieces from the Staffordshire Hoard ✨?✨) and partly, due to the way it’s laid out, because it is exceptionally slow moving.

To see any of the manuscripts properly, you have to lean over them and peer. Unfortunately, the explainers on each case are positioned right in front of the manuscripts. So first you have to stop and read the explainer, then lean over and peer.

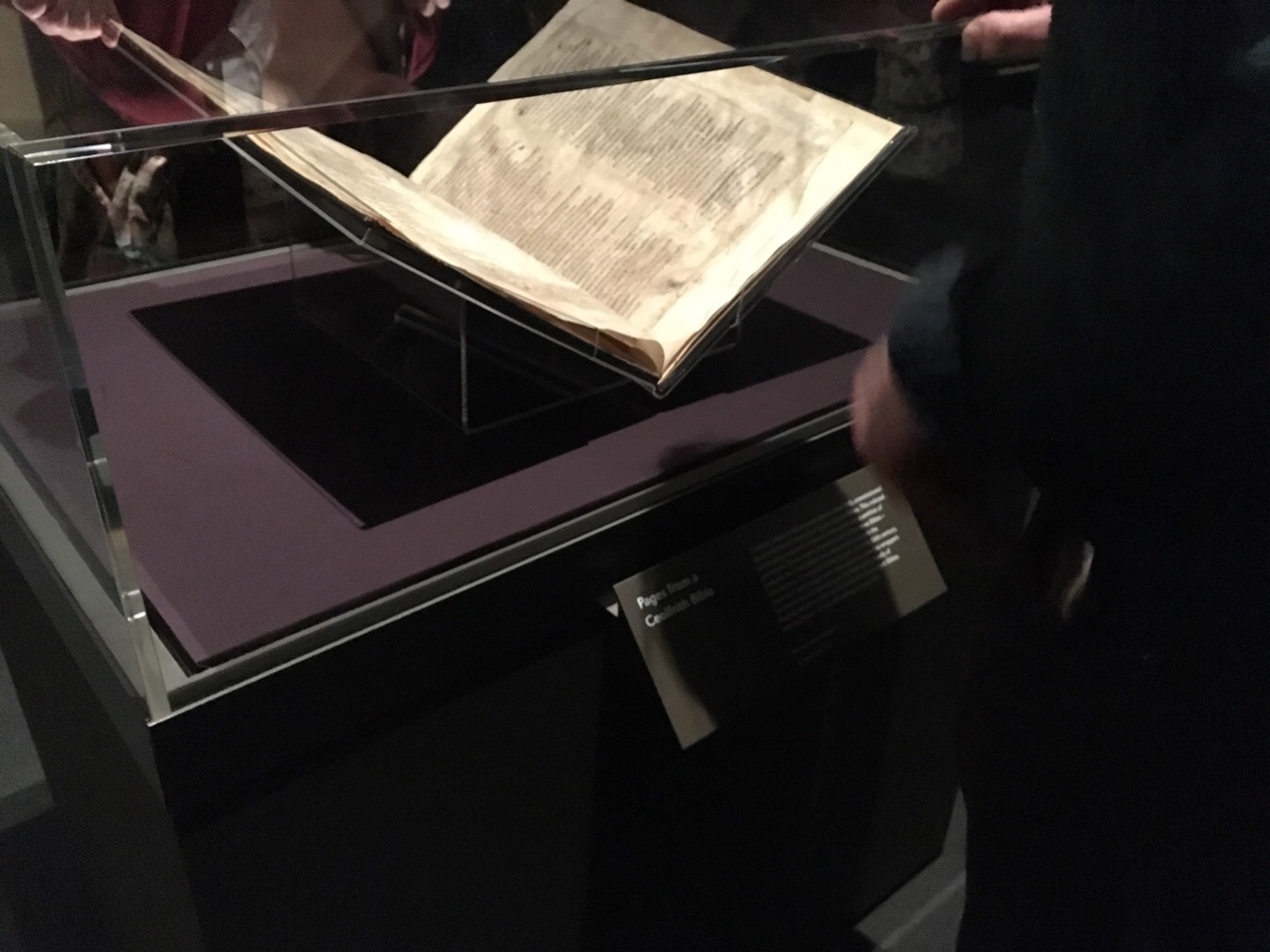

This means that when you’re looking at the exhibits, you’re blocking anyone else from reading the introductory explainer. See below – the nice chap in front of me couldn’t help but block it when it was his turn – which means it takes twice as long to see each exhibit as it ideally would.

It’s a small thing, but it really slows the flow of people through the exhibition and it also means you feel pressured to move on before you’re ready.

So leave at least a couple of hours (at least!) and be patient. But that’s small beer compared to the joy of seeing such unique and precious documents all together in one place.

(Oh, the British Medieval History group on Facebook recommends buying the exhibition catalogue in advance so you can prep beforehand – we found this a really good tip too.)

We were all quite blown away by the exhibition – here’s my dad pausing for breath afterwards. (Dear The Snowman – sorry he nicked your hat.)

So we went around the corner and had curry and non-alcoholic cocktails at Dishoom. (Well, Ted and I did. The Mothership had a proper one, obvs.)

Turns out a virtuous martini is actually much nicer than a real one … #dryjanuary Then home through one of the best tube tunnels in London.

Back in the 21st century, but dreaming of the ninth …

Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War is on at the British Library until 19 February. It’s spectacular.

Leave a Reply