On Saturday, Ted and I went to the V&A to see the Opus Anglicanum exhibition.

It was a miserable, wet day and all of London was seeking refuge inside.

Queuing for embroidery? Umm …

Sadly (fortunately?) they were all queuing for the Records and Rebels 1966-1970 exhibition, which was nice, because it meant the other one was much quieter.

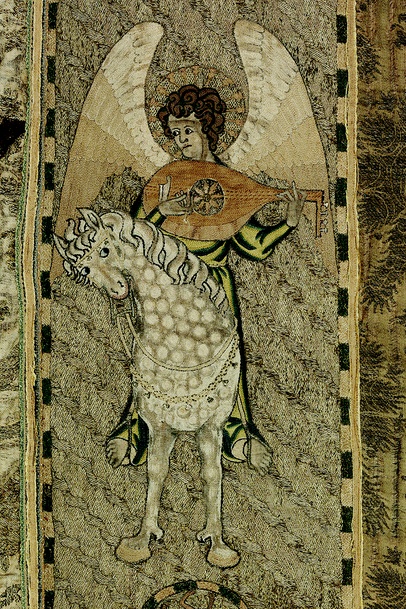

It’s a very lovely exhibition of extremely fragile and precious English embroideries, created between 1100 and 1550. Some of them are over 900 years old (!!) and it’s quite amazing that they have survived this long.

Opus Anglicanum exhibition. image (c) Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The work of medieval embroiderers was only really rediscovered and valued after Catholic emancipation, which culminated in the Roman Catholic Relief Act of 1829. This process returned many rights to Catholics in the United Kingdom, including the right to own property, to vote (above a certain income) and to sit in Parliament. Catholic emancipation led to a revival of interest in Opus Anglicanum in Victorian times, which, conveniently, was when the V&A was started, and so they were able to acquire significant works and thus holds the biggest collection of Opus Anglicanum in the world.

The exhibition is supplemented by works lent from across the UK and Europe and although it’s not enormous, there is a lot to see. Again, it was nice that the exhibition was quiet-ish, because we could get up really close to the embroidery and see the stitching.

The Syon Cope, 1310-1320. Image (c) Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Many pieces are embroidered with silver, gold or gilded thread. Some have, or had, jewels – cabochons, pearls and so on – stitched or attached to the fabric. Though some works are faded, others still show glorious colour. All have wonderful patterns and drawings and all are unique.

Many pieces are stitched on a linen base, or “ground”. Some of the finer ones have grounds of silk velvet, which in many cases has eroded quite significantly. In some works, these reveal the original patterns drawn onto the ground fabric where they would have originally sketched the pattern to be embroidered. There are ones where the hands or feet of embroidered revered figures, such as Jesus or Mary, had been eroded, perhaps by people touching the cloth during prayer or while requesting a blessing.

The Tree of Jesse was a popular motif – its intertwined leaves could hold a variety of figures or motifs representing the commissioner’s desired thoughts or messages.

Detail from the Syon Cope, 1310-1320. (c) Victoria and Albert Museum, London

My favourite piece featured some very grand lions which would have adorned a royal horse – possibly the king’s – at Edward III’s court. They had wonderful claws, big googly eyes and lolling pink tongues. The couch work and built-up embroidery on the lions and on other pieces was so intricate that it was hard to see the individual stitches, and the effect is magnificent.

It was interesting to discover that embroideries for the church were finer than those for the royal court – apparently, court work had to be turned around more quickly. (Fast fashion, huh.)

Detail from the Steeple Aston Cope, 1310-1340. (c) Victoria and Albert Museum, London

There is also something very moving about seeing works that have been created by hands the best part of a thousand years ago. Whether these works were created in daylight or at times by candlelight, it made me wonder what it was like to have stitched so meticulously for hours on end. It must have caused eyestrain, probably backache, certainly hand cramps and potentially, ultimately, the loss of sight.

I would recommend the exhibition highly to anyone who is interested in embroidery, church history, textiles or handicrafts. It is a window into a lost age, lost skills and a loss in the valuing of such intricate and precious creations.

Opus Anglicanum is at the Victoria and Albert Museum until Sunday, 5 February. Admission is £12 for adults.

Pro tip: If you’re going to Records and Rebels instead, maybe don’t go on a rainy weekend …

Leave a Reply